The Tuesday Afternoon Realization 🤔

I met Brynja on a Tuesday afternoon when Manchester was doing that thing it does—grey skies threatening rain but never quite committing. She walked in with the sort of composure that immediately told me she’d spent considerable time convincing herself she was fine, which is precisely the moment I know someone isn’t.

She described her life like someone trying to win an argument with themselves: good job, interesting hobbies, friends who matter, a self-image that was frankly enviable. And underneath it all? A longing for romantic intimacy that she couldn’t quite shake, no matter how many times she’d reasoned with herself about it. “I don’t see it as my main goal,” she said, with the kind of careful precision that suggested she’d rehearsed this sentence many times—in front of mirrors, during shower conversations with herself.

What struck me wasn’t the contradiction between what she was saying and feeling—that’s nearly universal. What interested me was her particular flavour of frustration. She didn’t want reassurance that romantic love wasn’t important. She didn’t want affirmations that she was enough as she was. What she wanted, though she hadn’t quite named it, was permission to feel the ache without feeling broken by it.

The Architecture of Longing 🏗️

Here’s what people don’t realize about emotional longing: it’s not actually about the thing you’re longing for. Well, it is—but not in the way you think.

Brynja had constructed a fairly rigid emotional frame around romantic partnership—an interpretive lens that had become so familiar it felt like truth. Within that frame lived predictable sensations: the Sunday evening quiet, the way affection looks in other people’s Instagram stories, the particular ache of waking alone. These weren’t just feelings; they were encoded packages of physical sensation, emotional weight, narrative meaning, and need.

She could articulate all of it intellectually. She could tell you why she didn’t need romantic love to complete her. But her nervous system—shaped by years of absorbing cultural stories about partnership and belonging—had written its own script. A set of automatic responses that felt inevitable, like the way your body automatically reaches for a handrail when you stumble.

What fascinated me in our early sessions was watching her become frustrated with her own wisdom. She’d reach for the tools she knew worked—self-care, rational perspective, time with friends—and they’d help, briefly, like applying a plaster to something that wanted deeper attention. Then the longing would surface again, and she’d feel like she was failing at being the self-aware, well-adjusted person she’d constructed.

The issue wasn’t that her tools were wrong. It was that she was trying to eliminate a feeling using frameworks designed for management, not understanding.

The “I’m Fine” Paradox (Especially for Women) 💪

There’s something peculiar that happens when women build genuinely okay lives in most areas. We develop a kind of cognitive sophistication that can actually work against us. We can see our loneliness from multiple angles—sociological, psychological, practical—and yet none of those angles seem to touch the raw fact of wanting something we don’t have.

I’ve noticed this pattern particularly in women who’ve built lives of genuine independence and accomplishment. There’s an unspoken pressure we absorb: integrate romantic desire into a narrative of self-sufficiency rather than genuine need. As if wanting partnership is somehow a failure of the independence project.

We’ve swung so far from one extreme—woman needs man to complete her—that we’ve created another equally false one—woman should transcend the need for romantic love through sufficient self-development. Neither is true. Both are traps.

Brynja was caught in this particular snare. Her self-worth wasn’t dependent on having a partner, but her identity had become organized around the idea that it shouldn’t matter. There’s a crucial difference, though she couldn’t see it at first.

If you’re a woman reading this who’s built a good life, who’s independent and accomplished, let me be direct: wanting romantic partnership doesn’t diminish your independence. It doesn’t make you less feminist. It doesn’t mean you’ve failed at being self-sufficient. It means you’re human.

The Distinction That Changes Everything ✨

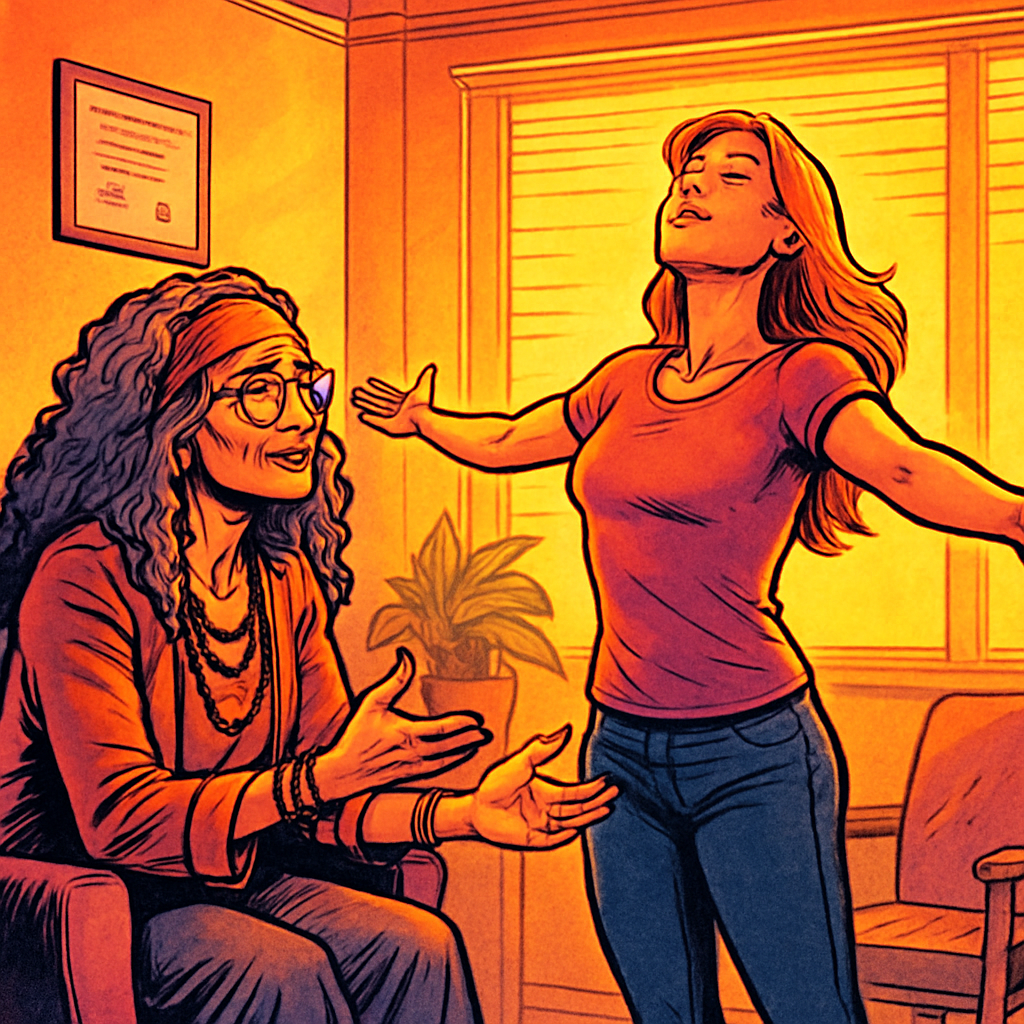

One day, maybe six weeks into working with Brynja, I asked her a question that seemed simple but shifted something fundamental. “What if,” I said, “your loneliness isn’t actually telling you that you’re incomplete? What if it’s telling you that you’re human?”

She looked at me the way people do when you’ve said something obvious that somehow no one had bothered to say before.

We began separating two things she’d been treating as identical: the desire for romantic intimacy, and the belief that this desire indicated some kind of failure or incompleteness. One is a genuine human need. The other is a story she’d internalized about what that need meant.

This is where emotional granularity becomes useful. Instead of the overwhelming blob of “I’m lonely and this means something’s wrong with me,” we could distinguish between specific components: the physical sensation of longing, the narrative layer interpreting longing as pathological, the identity question of whether she could want something and still be independent, the relational need for reciprocal tenderness (which isn’t quite the same as needing someone to complete her).

These are different things with different solutions. And here’s the thing: not all of them require solutions. Some of them just require honest acknowledgment.

The Invisible Architecture We Absorb 🎭

What became clear as we worked was that Brynja’s struggle wasn’t primarily about attachment style or cognitive distortion, though both played a role. It was about invisible structures—the unspoken rules she’d absorbed about what a self-aware, independent woman should want and should be able to transcend.

She’d internalized a particular version of empowerment that didn’t leave room for wanting things she couldn’t control. And romantic partnership is perhaps the ultimate example of something you can’t control. You can work on yourself, expand your social circles, stay open to possibility—but you cannot will another person to love you.

There’s something almost superstitious about how we handle this. We create elaborate belief systems—get yourself right first, then love will come; lower your standards; stop looking so hard; be yourself more authentically—as if we can somehow game a system that fundamentally involves another person’s autonomous choice.

Brynja had absorbed all of these narratives and was trying to organize her emotional life around them, which meant she was trying to organize her emotional life around a fiction.

The work wasn’t about changing what she wanted. It was about creating space between her desires and the stories she’d built around what those desires meant.

The Middle Path (The Only Honest One) 🛤️

Here’s the principle I offered her, and I’ll offer it to you: your emotional needs don’t get to vote on your values, but they do get to speak.

What I mean is this: you don’t have to organize your entire life around acquiring something you want. But you also don’t get to pretend you don’t want it. The middle path—the only honest one I’ve found—is to acknowledge the wanting while building a life that doesn’t collapse if you don’t get it.

This sounds impossibly complicated, but it’s actually simpler than the alternative she’d been attempting: trying to reorganize her emotional experience to match her intellectual commitments. She was trying to feel differently by thinking differently, which is like trying to change your accent through determination alone. It doesn’t work that way.

By our eighth session, she was asking entirely different questions. Not “why do I still feel this?” but “what am I actually needing here?” Not “how do I stop wanting this?” but “how do I want this without it becoming everything?” These questions have entirely different emotional landscapes.

She started developing what felt like an intentional relationship to her loneliness. Not wallowing in it, but also not white-knuckling her way past it. She’d have evenings where she let herself actually feel the ache, without the secondary layer of judgment. Other nights she’d deliberately build social connection that fed a different kind of intimacy hunger. Both felt true. Both needed room in her life.

The Exhaustion of Being “Fine” 😴

There’s a strange thing that happens when people are genuinely competent and self-aware. They develop the ability to be quite comfortable being uncomfortable. They can rationalize their loneliness into a kind of noble melancholy. They can appreciate their solitude in ways that are sophisticated and genuine, and yet underneath it, sometimes there’s just the simple human wish to be held.

We don’t talk enough about how exhausting it is to be the kind of person who’s supposed to be fine with everything. Who’s supposed to transcend basic human longings through sufficient self-development or spiritual practice or feminist consciousness.

For women especially: this performance is often invisible labour on top of everything else you’re already managing.

Brynja was tired. Not of being alone—she actually quite liked her own company. She was tired of managing the narrative about being alone. Tired of the work it takes to hold together the story that her worth isn’t touched by her relationship status, while simultaneously trying not to feel the deep wanting for connection that contradicted that story.

The shift came when she stopped trying to reconcile these two truths and just lived them instead. Yes, she was enough as she was. Yes, she also wanted something she didn’t have. Both of these could be true without either invalidating the other.

The Wry Closing Thought 🎭

As Oscar Wilde might observe, the universe has a particular sense of humour about longing: we become most attractive to others precisely when we stop trying so desperately to be attractive to them. But I suspect this is less about the law of attraction and more about something simpler: desperation is incompatible with presence.

When Brynja stopped treating her loneliness as a problem that needed solving, when she stopped performing the role of the woman who was totally fine without romantic love, something shifted in how she showed up in the world. Not because wanting less made her more desirable—that’s the superstition—but because she was finally available to herself and others in a way she hadn’t been when she was busy managing her emotional narrative.

The universe, I’ve found, doesn’t reward the performance of wholeness. It merely reflects back the genuine article.

- Evidence brief | How can people cope with loneliness?

- A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Reduce Loneliness – PMC

- Does stimulating various coping strategies alleviate loneliness …

- Effective Coping with Loneliness: A Review – Scirp.org.

- Loneliness among college students: examining potential coping …

- [EPUB] Exploring how children and adolescents talk about coping strategies …

- Navigating loneliness: the interplay of social relationships and …