The Coffee Shop Conversation 🤍

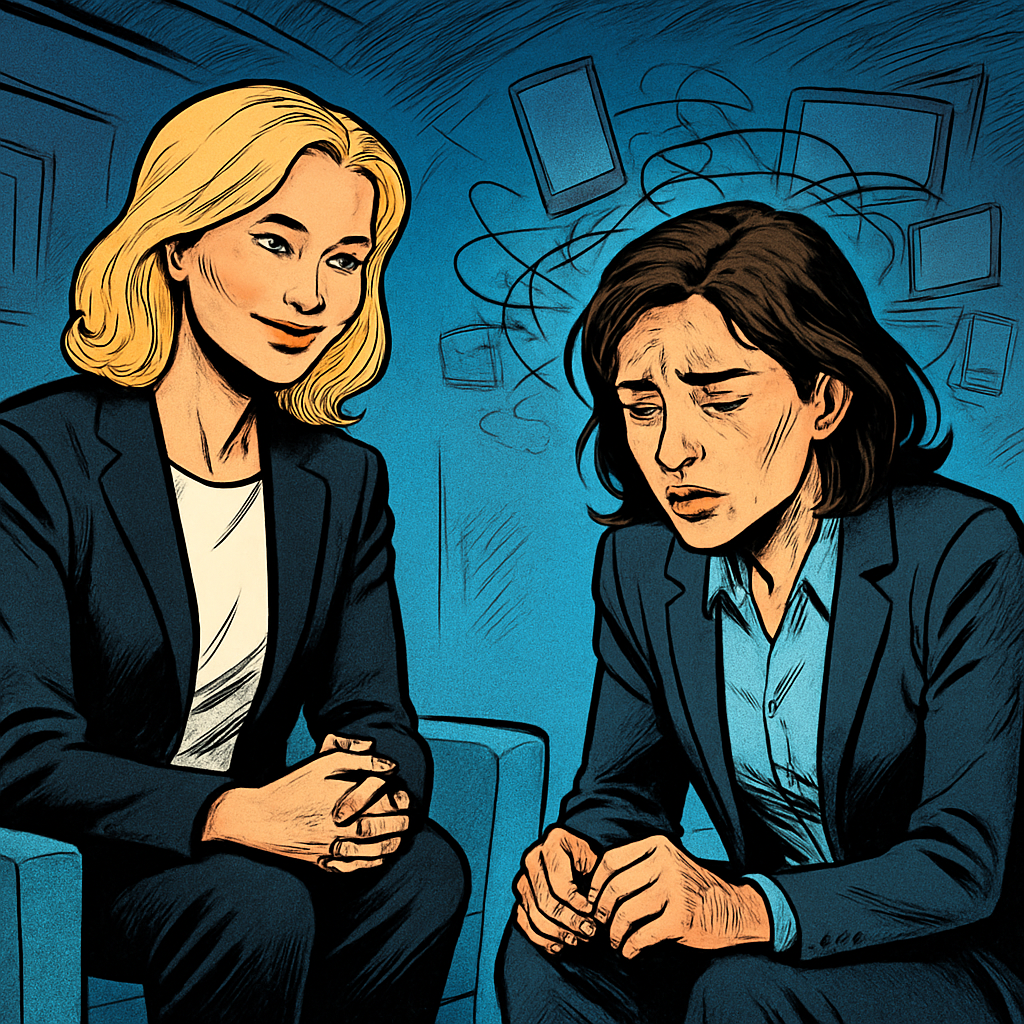

It was a Tuesday at 4:47 p.m. when Saskia arrived—three minutes early, as high-achieving professionals always do—her perfectly pressed Reiss blazer somehow still crisp despite the humid Manhattan afternoon. She ordered an oat milk cappuccino and carried it upstairs with careful precision.

Within minutes, she was mid-sentence about TikTok discourse and something called a “discourse ecosystem” that seemed to be actively ruining her ability to enjoy her own life. “Everyone’s talking about age gaps,” she said, not quite meeting my eyes. “And I can’t stop thinking about it. I feel anxious. I feel wrong somehow. But statistically, these relationships are rare, right? So why does it feel like they’re everywhere?”

She took a sip of her now-cold coffee. “Why can’t I just… stop caring what the internet thinks?”

The Modern Paradox 📱

This is what nobody tells you about professional success: building an empire means absolutely nothing when your emotional architecture is being quietly rewired by an endless feed of other people’s opinions masquerading as universal truth.

Saskia was sharp—the kind of sharp that makes you money—but she was drowning in what I call the modern paradox of information. We have more data than ever before, yet we’re somehow more confused about what’s actually real versus what merely feels omnipresent.

When Emotional Responses Feel Irrational 💭

What was actually happening with Saskia wasn’t complicated once we stopped talking about the internet and started talking about her nervous system. She was experiencing what we might call emotional bytes—little clusters of physical sensation, emotional charge, and story-narrative that fired every time certain topics crossed her feed. Her body would tense. Her thoughts would spiral. Then, in that crucial gap between sensation and response, she’d feed herself a narrative: I should be able to ignore this. I’m overthinking. There’s something wrong with me for caring.

But here’s what we’ve all been dancing around: your emotional responses aren’t irrational just because the trigger seems trivial. Your mind isn’t broken for being affected by information that speaks to your deepest uncertainties about identity, belonging, and whether your own choices will someday become the subject of everyone else’s moral outrage.

The Noise We Mistake for Signal 📊

Saskia’s anxiety wasn’t really about age-gap relationships. It was about something far more human: the way our brains are wired to notice patterns, especially ones that repeat constantly in our visual field. When something appears frequently enough in your information diet, your mind stops asking “Is this actually common?” and starts assuming “Everyone must be talking about this for a reason.”

The vivid examples stick. The statistics fade. And suddenly you’re spiraling at midnight about a demographic phenomenon that affects maybe 5 percent of actual relationships, convinced it’s somehow the moral litmus test of our time.

This is what happens when we mistake accessibility for prevalence. Your feed shows you hundreds of discourse threads about something, and you think you’re seeing a reflection of reality. You’re not. You’re seeing what algorithms decided you should see—which is a fundamentally different thing.

The real problem? Saskia had internalized a particular emotional frame—a lens through which she interpreted all information about relationships—that made her hyper-attuned to judgment, deviance, and moral danger. Every article felt like an indictment. Every conversation felt like a test. She wasn’t just reading about relationships; she was running every fact through a security scanner set to hair-trigger sensitivity.

And underneath that frame lay pure, unexamined terror about what people would think of her if they knew what she actually wanted.

The Identity Trap We Set for Ourselves 🪞

Here’s where it got interesting. Saskia would come in talking about media exposure and anxiety management, but what she was really grappling with was something far more intimate: the gap between who she thought she should be and who she actually was—or might be, or feared she might want to be.

We don’t just absorb information neutrally. We filter everything through invisible emotional scripts—automatic behavioral patterns that feel so natural we rarely question them. Saskia had a script that said: I must be seen as enlightened, progressive, and aligned with current moral standards. The moment she encountered discourse suggesting that age-gap relationships were problematic, that script activated.

Her nervous system automatically searched her own experience and preferences for anything that might contradict that approved identity. Did she have a thing for older men? The anxiety spiked. Had she ever felt attraction to someone significantly younger? Immediate shame—not because she’d done anything wrong, but because her emotional frame had already decided these preferences were suspect.

The irony was exquisite: her anxiety about judgment had become its own judge. She was policing herself more ruthlessly than any comment section ever could.

I asked her one afternoon: “What would it mean about you if you were attracted to someone ten years older? Or younger?”

She went very still. “That I’m… shallow? That I’m not evolved?”

There it was.

Understanding What Your Anxiety Is For 🔍

What we worked on in subsequent sessions wasn’t how to ignore the discourse or manage media consumption. What we actually worked on was understanding what her anxiety was for. Every emotional response contains information. Her panic about age-gap conversations was trying to tell her something about her needs hierarchy—about what she actually required from relationships versus what she thought she should require.

Some people need stability. Some need novelty. Some need to feel chosen by someone with proven success and resources. None of these are moral failures. They’re just needs—invisible structures running underneath our behavior, shaping what we want before we even know we want it.

Saskia’s anxiety wasn’t a sign that her preferences were wrong. It was a sign that she’d internalized someone else’s moral framework and was using it to interrogate her own desires. Every moment spent spiraling about discourse was a moment she wasn’t actually thinking about her values, her attractions, her non-negotiables in a partner.

The work was about developing what I call emotional granularity—the ability to break down that overwhelming blob of anxiety into smaller, more specific experiences. Instead of “I feel anxious about age-gap discourse,” we identified: I feel anxious because I’m afraid I’m attracted to people my social circle would judge. I feel anxious because I’m not sure if my preferences are authentic or internalized. I feel anxious because I don’t know who I actually am separate from what I should be.

Once we made those distinctions, we could actually work with something real instead of chasing a ghost.

Reclaiming Your Own Moral Authority ✨

The internet discourse about age gaps isn’t actually about age gaps. It’s about control, identity, and the way we use moral certainty to feel safe in an uncertain world. If we can declare something universally wrong, then we don’t have to think about our own complicated motivations. We get to be the good person by default.

But that strategy requires constant vigilance. It requires reading every thread, monitoring your own thoughts, ensuring you’re on the correct side of whatever line has been drawn this week. It’s exhausting. And it’s a form of outsourcing your moral agency to people who don’t know you, don’t love you, and will never have to live with the consequences of your choices.

What Changed 🌱

By the end of our work together, Saskia wasn’t “fixed”—and honestly, that’s not how any of this works. But she’d developed the ability to notice when she was operating from her own values versus when she was running someone else’s emotional script. She could feel the anxiety coming and ask: Is this mine? Or is this me defending against judgment? She could distinguish between genuine ethical concerns and internalized social-norm anxiety.

For perhaps the first time in years, she could sit with her own desires without immediately running them through a moral filtration system. Did that mean she suddenly had clarity on what she wanted in a partner? Not immediately. But she could start looking without narrating the search as a moral failure. She could notice her attractions without the accompanying shame script. She could be a person with preferences instead of a person constantly auditing whether her preferences were acceptable.

The discourse is still out there. The articles still appear. The opinions keep flowing. But Saskia stopped treating her social media feed like a referendum on her character. She started treating it like what it actually is: noise generated by an algorithm designed to keep her engaged, not informed.

Sometimes the bravest thing you can do in this culture isn’t stating your position loudly. It’s getting quiet enough to hear what you actually think beneath the roar.

— Lola Adams, reminding you that the voice criticizing your choices most harshly is usually the one you inherited from people who were terrified of judgment themselves.

- Many Americans have engaged in age-gap dating

- Big Age-Gap Relationships Are Having a Moment

- Age disparity in sexual relationships

- [PDF] AGE GAP RELATIONSHIPS IN ADOLESCENCE – Long-Term Effects

- Age disparity in couples and the sexual and general health of … – NIH

- Growing share of US husbands and wives are roughly the same age

- [PDF] An Exploration of Age-Gap Relationships in Western Society