The Emotional Architecture Behind Custody Disputes 🏛️

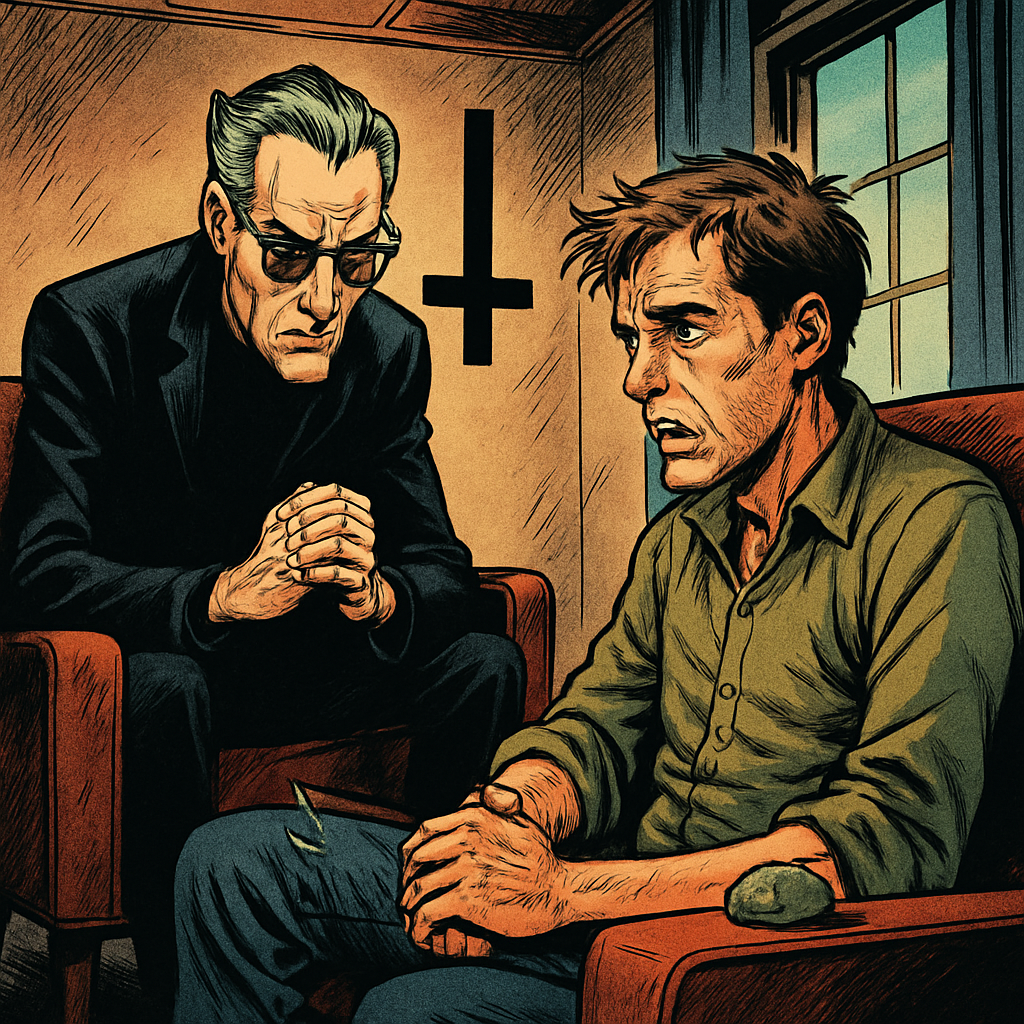

Custody disputes rarely concern custody at all. They’re about control—who decides the shape of a child’s week, the geography of belonging, the mathematics of presence. Tristan sat in my office on a Tuesday afternoon, his knee bouncing with kinetic anxiety. He’d been a banker before the divorce. Numbers had once made sense to him. Now he couldn’t count anything that mattered.

“I just want to know if fifty-fifty is going to destroy him,” he said, avoiding my gaze. “The research says it’s good for kids, but it doesn’t account for the two-and-a-half-hour distance. It doesn’t factor in my son asking why he has to leave on Sunday night.”

I knew what that did to a child. But first, I needed to understand what it was doing to Tristan.

The Emotional Frame Masquerading as Concern 💭

Most therapists would’ve reassured him with statistics. The research is sound—shared custody arrangements, when low-conflict, correlate with better outcomes: higher self-esteem, reduced behavioral problems, stronger relationships with both parents.

But Tristan wasn’t interested in research. He was interested in the story he’d already written about what would happen.

What I witnessed was an emotional frame—interconnected emotional patterns organized into a predictive lens. This frame contained the physical sensation of Sunday-night dread (anticipatory anxiety encoded in his nervous system), the emotional charge of guilt, and beneath it all, a narrative that his absence meant being less of a father.

“Tell me about your own father,” I said.

Tristan’s knee stopped bouncing. That’s when I found it.

“He was there. Every day. Even when my parents should’ve divorced, they didn’t, because my father believed that’s what fathers do.”

The invisible structure wasn’t about his son’s stability. It was about Tristan’s identity needs—the requirement to prove himself through continuous physical presence, to validate his worth as a father through metrics that felt like love but tasted like obligation. The anxiety about 50/50 wasn’t about logistics. It was about the terror of becoming something less than what he’d internalized as “a real father.”

When Legitimate Concerns Hide Deeper Fears 😰

Tristan’s concerns about his son’s stability weren’t baseless. The research confirms it: very young children (his son was 2.5) benefit from a stable primary residence and minimal transitions. Geographic distance presents real logistical challenges. These aren’t neurotic fantasies—they’re reasonable parental observations.

But here’s what was happening: Tristan was using legitimate concerns as containers for illegitimate emotions. He was smuggling his own abandonment wounds, his own fears about being “enough,” into the shape of reasonable parental worry. I call this emotional granularity in reverse—collapsing a complex internal state into a single, acceptable narrative.

“What would it mean,” I asked, “if your son thrived in a 50/50 arrangement? What would that say about you as a father?”

His body answered—shoulders tightening, jaw clenching, that trapped-animal energy returning to his eyes. What it would mean was that presence wasn’t everything. That love could be distributed across time and space. That he could matter deeply while being away. These truths threatened the emotional script he’d inherited—the one that said real fathers don’t leave.

The Suppressed Desire for Your Own Life 🗽

Here’s what Tristan couldn’t say out loud, and what most custody-anxious parents can’t either: underneath the concern for his son’s stability was a suppressed desire for his own stability. For a life not entirely organized around handoff choreography. For the possibility of a partner, a career move, a night not consumed by full-time single parenting.

This desire had been thoroughly demonized—coded as selfish, as abandonment, as the thing “bad fathers” feel. It lived in the shadow, wearing the mask of concern for his son.

The research supports a counterintuitive truth: fathers who share custody responsibilities more equally experience lower parental stress and better overall well-being. That improved, less-frantic version of himself is better for the child. Tristan’s psychological stability mattered. His capacity to show up as a regulated, present father (even 40% of the time) outweighs the mythology of constant presence.

He had to reclaim that desire. Recognize it not as selfish but as self-honoring.

Building Parallel Parenting Structures 🌉

The research identifies a critical variable: co-parenting conflict damages children, not the custody arrangement itself. Tristan’s obsessive focus on 50/50 logistics was displacement—avoiding the actual conversation he needed with his son’s other parent about how to parent together despite not being together.

The work shifted from introspection to what I call “Lesser Magic”—the ritualistic manipulation of everyday dynamics to create the conditions you actually want. For Tristan, this meant establishing parallel parenting structures: agreed-upon routines that didn’t require constant communication, clear decision-making boundaries, and reduced ambient conflict that his son was absorbing.

“Your son doesn’t need you present 100% of the time,” I told him. “He needs you regulated 100% of the time. Which version of you is he more likely to get—the exhausted, resentful father, or the engaged father who shows up rested and present for 40% of the days?”

We mapped out what this would look like: clear handoff rituals with transition time, consistent bedtime routines in each home, age-appropriate language for explaining the schedule. These are the emotional scripts that replace anxiety scripts—new predictive models his son’s nervous system would encode: not “Dad is leaving me” but “This is how we love across distance.”

Ritual: Transforming Sunday Night Dread 🪨

Ritual doesn’t fix custody arrangements. But it can transform how you hold them in your body and psyche. For Tristan, I suggested a practice for his Sunday evenings—the moments most saturated with dread.

Before his son left, he would take a small stone from his garden and hold it while naming what he was sacrificing: “I release my need to be the constant presence. I release the script that says my worth is measured in hours.”

Then he would give the stone to his son as a connection object: “This stone knows you. It knows our garden. You take it, and you carry me with you—not because I have to be physically there, but because love doesn’t actually have a time limit.”

This is positive disintegration—the psychological tension necessary to move beyond inherited patterns. It integrates the rejected desire (wanting his own life) with parental love (wanting what’s best for his son) into a coherent narrative his nervous system could believe. It creates a new emotional pattern where leaving becomes an act of love, not abandonment.

Honor Through Right Action, Not Constant Presence ⚔️

In old Norse traditions, honor wasn’t about proximity—it was about keeping your oath. A father’s oath to his child isn’t “I will be here every day.” It’s “I will show up as my best self, consistently and reliably, within the arrangement we’ve made.”

The cultural mythology equating fatherhood with constant presence is a relatively modern invention—one that conveniently exhausts fathers and traps them in resentment. The more honest framing comes from wyrd—the idea that your fate is shaped by the choices you make and the will you exercise.

Tristan’s wyrd as a father wasn’t determined by a custody agreement. It was determined by whether he chose to show up with intention, authenticity, and his own life intact. A father who’s present but depleted and resentful is less of a father than one who’s genuinely engaged for the time he has.

By the time Tristan left my office, he’d moved from “How do I prevent this custody arrangement from destroying my son?” to “How do I make sure I show up as the best version of myself within this arrangement?”

That’s the shift from victim to author. From anxiety to agency.

What his son actually needed wasn’t a father who was always there. It was a father who was fully there when present—and genuinely living his own life when he wasn’t.

Hail yourself, Tristan. Hail your becoming.

—Lucian Blackwood

Hail Yourself, Hail the Will That Shapes Your Fate

- Does-Social-Science-Research-Support-a-Presumption-of- …

- Embracing 50/50 Custody is the Best for Children

- The Case for 50/50 Timesharing When Parents Divorce

- Research Shows That True Joint Custody Between Parents …

- How Custody Arrangements Shape A Child’s Mental Health

- Does Shared Parenting Help or Hurt Children in High …

- The Long-term Impacts of Joint Custody Arrangements